Galileo Forgery’s Trail Leads to Web of Mistresses and Manuscripts

When the University of Michigan Library announced last month that one of its most prized possessions, a manuscript said to have been written by Galileo around 1610, was in fact a 20th-century fake, it brought renewed attention to the checkered, colorful career of the man named as the likely culprit: Tobia Nicotra, a notorious forger from Milan.

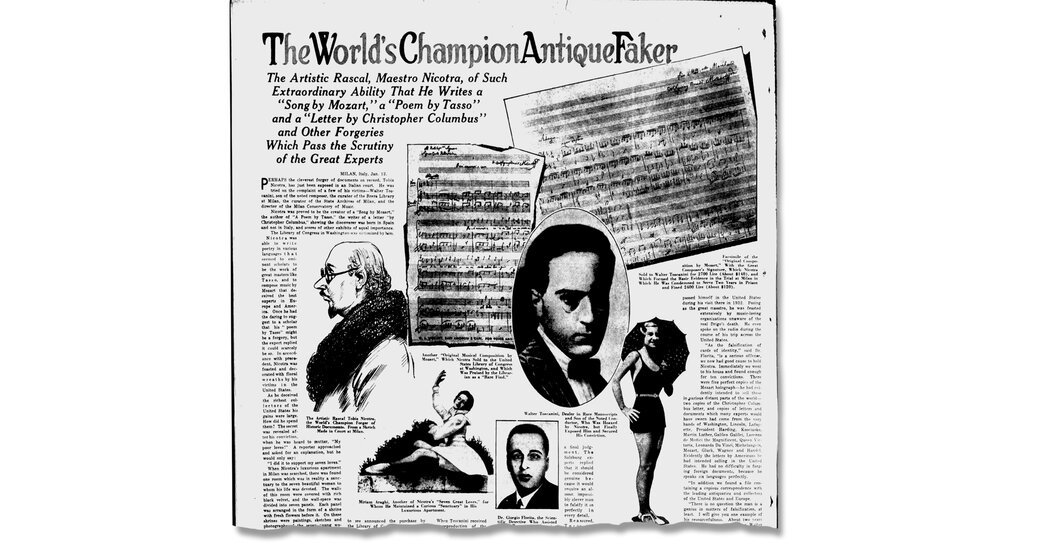

Nicotra hoodwinked the U.S. Library of Congress into buying a fake Mozart manuscript in 1928. He wrote an early biography of the conductor Arturo Toscanini that became better known for its fictions than its facts. He traveled under the name of another famous conductor who had recently died. And in 1934 he was convicted of forgery in Milan after the police were tipped off by Toscanini’s son Walter, who had bought a fake Mozart from him.

His explanation of what had motivated his many forgeries, which were said to number in the hundreds, was somewhat unusual, at least according to an account of his trial that appeared in The American Weekly, a Hearst publication, in early 1935.

“I did it,” the article quoted him as saying, “to support my seven loves.”

When the police raided Nicotra’s apartment in Milan, several news outlets reported, they found a virtual forgery factory, strewn with counterfeit documents that appeared to bear the signatures of Columbus, Mozart, Leonardo da Vinci, George Washington, the Marquis de Lafayette, Martin Luther, Warren G. Harding and other famous figures.

Investigators had also found a sort of shrine to his seven mistresses, at least according to The American Weekly. The article described a room with black velvet-covered walls, with seven panels featuring paintings, sketches and photographs of the women — one of whom was said to be a “novelty dancer,” and another an “expert swimmer” — with fresh flowers in front of each. “The pictures in some cases displayed their physical attractions with startling frankness, but they were in general highly artistic,” the article noted.

“Incidentally,” the publication added, “he had a wife.”

Over the years Nicotra’s counterfeits have fooled collectors and institutions, sown confusion, and been denounced by the esteemed Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, who collected musical manuscripts and who wrote an article in 1931 naming Nicotra as a forger. Now Nicotra is back in the news, thanks to the Galileo forgery in Michigan, which was unmasked by Nick Wilding, a historian at Georgia State University who showed that the paper it had been written on had a watermark dating from the late 18th century, more than 150 years after Galileo supposedly wrote it. He also linked it to several other Nicotra forgeries.

“Either he thought he was just invincible, or he was maybe just incredibly desperate,” Wilding, who is working on a biography of Galileo, said of Nicotra. While other forgers have been more prolific, Wilding said, few have been as daring — or as talented.

“Everything Nicotra does is plausible; there are no jarring anachronisms,” he said. “He knows enough to try and get it right.”

There is relatively little concrete information about Nicotra, and, given that he was a professional forger, the existing documentary evidence must be taken with a grain of salt. “The facts just seem to slip away from him,” Wilding said. While some accounts say he was 53 at the time of his trial, a birth certificate suggests he may have been 44. Contemporary news accounts, and interviews with several scholars who have studied him, however, begin to give some sense of the man and his prolific career.

A courtroom sketch of Nicotra that appeared in The American Weekly portrays him as a balding, thin-faced man with glasses perched on a pointy nose, sporting a mustache and goatee, and wearing either a thick scarf or some kind of furry, Astrakhan-like collar on his coat.

Nicotra cast a wide net in the types of documents he counterfeited, and seems to have possessed real talent and learning. He forged a poem he claimed was by the Italian Renaissance poet Tasso, musical manuscripts by leading composers, and was even said to have started a minor international incident by creating a fake Columbus letter identifying his birthplace as Spain, not Italy, prompting the mayor of Genoa to write a lengthy rebuttal reaffirming Columbus’ Italian ancestry.

An account of his 1934 conviction by The Associated Press, which ran in The New York Times under the headline “Autograph Faker Gets Prison Term,” described how Nicotra operated: “His method was to visit the Milan Library and tear out the fly leaves of old books or steal pages of manuscript and write on them the ‘autographs’ of famed musicians. The librarians of Milan testified that he had ruined scores of their books.”

In 1928, he sold what appeared to be a signed Mozart aria called “Baci amorosi e cari,” supposedly written by the composer at age 14, to the Library of Congress.

“It was so special because first of all it was unknown, so it wasn’t reported in any of the thematic catalogs of Mozart at that time,” Paul Allen Sommerfeld, a music reference specialist at the Library of Congress, said in an interview. “He claimed that he found this manuscript and then published the song.”

The library paid $60 for the document, which was later believed to have been composed by Nicotra himself.

Nicotra said he was the son of a botany professor, and he wrote in one letter that he had graduated with a music degree from a conservatory in Naples in 1909. “We don’t know whether that’s a true fact or not,” Wilding said.

When he published his biography of Toscanini in 1929, early critics noted that it contained a number of errors. It is seen as even more unreliable today.

“It’s mostly invented conversations and so on,” said Harvey Sachs, the author of a definitive 2017 biography, “Toscanini: Musician of Conscience.” “Just made-up stuff.”

In 1932, Nicotra toured the United States while masquerading as Riccardo Drigo, an Italian conductor and composer who had been the conductor of the Imperial Ballet in Russia and who may be best remembered for the arrangement of “Swan Lake” he created after Tchaikovsky’s death. (The Associated Press reported that Nicotra had been “feted widely in the United States as the former orchestra conductor of the Czar of Russia.”) Apparently no one realized that Drigo had died two years earlier, in 1930.

“My main way of characterizing him would be ‘bold,’” said Erin Smith, who wrote her master’s thesis on Nicotra at the University of Maryland in 2014. “He was able to carry on with this for a good number of years.”

Nicotra was also known for forging works by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, an early-18th-century composer who died at the age of 26 and whose posthumous fame attracted forgers. One Pergolesi forgery wound up in the collection of the Metropolitan Opera Guild. When Christie’s auctioned it in 2017, it described it as an “intriguing forgery, once thought to belong to the hotly debated Pergolesi canon” and cited authorities who list it as “created by the prolific forger Tobia Nicotra.” It fetched $375.

The discovery of the Galileo leaves open the question of what happened to the many other forgeries Nicotra created, which he was quoted as saying could number as many as 600.

“I don’t know if he did 600, but I’m sure he did more than the little we’ve found so far,” said Richard G. King, an associate professor emeritus at the University of Maryland School of Music, who has been researching Nicotra. “I don’t think people are willfully hiding these things, but it’s just hard to find them.”

Unless an institution has a record of buying documents from Nicotra, Wilding said, it may be hard to identify other forgeries. He suggested that documents by figures Nicotra habitually forged that lack clear provenance before the 20th century “are probably really worth looking at very, very closely.”

Nicotra eventually ran afoul of the law after selling the fake Mozart manuscript to Walter Toscanini, who persuaded detectives in Milan to investigate the case. Nicotra was convicted, fined 2,400 lire and sentenced to two years in prison.

Some accounts suggest that Nicotra was let out of prison early, because the Fascist government wanted his help forging signatures. That story, notes Wilding, “is just too good to be ignored, and maybe too good to be true.”