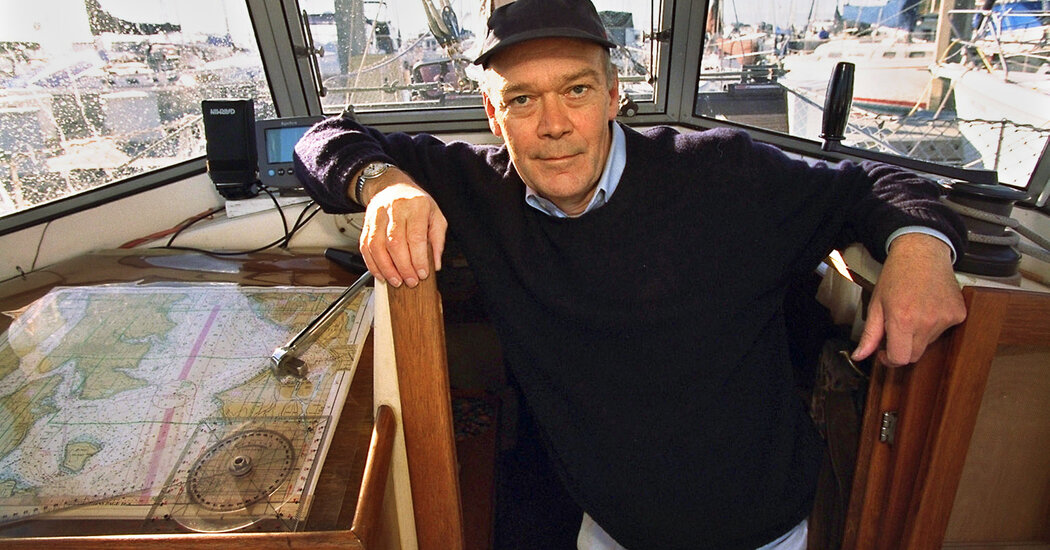

Jonathan Raban, Adventurous Literary Traveler, Dies at 80

Jonathan Raban, an acclaimed expatriate British writer known for his literary travels to the Middle East, down the Mississippi River, to Alaska’s Inside Passage and into eastern Montana, died on Tuesday in Seattle, where he had lived since 1990. He was 80.

Clare Alexander, his agent, said the cause was complications of a stroke he had in 2011.

Mr. Raban’s literary narratives of the places he visited and the people he met combined travelogue, memoir, reportage and criticism. What he was not, he insisted, was a travel writer.

“Travel writing seems to me a too-big umbrella, full of holes to let the rain in,” he told Granta magazine in 2008. “Anyone commissioned by a newspaper to write up meals and hotels in foreign holiday resorts is a travel writer. Anyone who does a guidebook is a travel writer.”

He had an affinity for V.S. Naipaul, Paul Theroux and Bruce Chatwin, whose books take the reader to places far and wide but transcend the travel genre.

“Chatwin and Sebald knew that ‘travel book’ and ‘travel writing’ were terms of literary abuse and did their best to rescue their books from the category,” Mr. Raban said in the interview. “I know that feeling.”

In a tribute in The Guardian, the English writer Philip Marsden wrote that Mr. Raban’s books offered a “view of the world that was both darkly comic and sardonic, delivered in prose that can pierce your heart with its accuracy.”

In “Bad Land: An American Romance” (1996), Mr. Raban explored how homesteaders were lured to settle desolate, desert-like counties in eastern Montana in 1907 and 1908, brought there by the railroad, but who, after a few thriving years, left in an exodus when the weather turned dry again. They left the prairie littered with the wreckage of their dreams.

“Their windows, empty of glass, were full of sky,” he wrote of the derelict houses he found. “Strips of ice-blue showed between their rafters. Some had lost their footing and tumbled into their cellars. All were buckled by the drifting tonnage of Montana’s snows, their joists and roof beams warped into violin curves.”

Reviewing “Bad Land,” Verlyn Klinkenborg wrote in The New York Times: “What makes the book so memorable, in fact, is Mr. Raban’s imaginative reach. He recaptures the hope, as well as the pure narrative momentum, of the coming of settlers in eastern Montana in the early 20th century, and he arrays it against their subsequent fate.”

“Bad Land” won the 1996 National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction.

In “Passage to Juneau: A Sea and Its Meanings” (1999), Mr. Raban sailed from Seattle to Alaska along the complicated coastal route called the Inside Passage. It turned out to be a complicated personal journey, as well, one that found him bruised by the end of his marriage to Jean Lenihan and the illness of his father, which interrupted the seafaring and prompted Mr. Raban to fly to England to be with him as he died.

Mr. Raban feared the sea, where he often found himself, but he was fascinated enough to find solace in it.

“I fear the brushfire crackle of the breaking wave,” he wrote, “as it topples into foam; the inward suck of the tidal whirlpool; the loom of a big ocean swell, sinister and dark, in windless calm; the rip, the eddy, the race; the sheer abyssal depth of the water, as one floats, like a trustful beetle planting its feet on the surface tension. Rationalism deserts me at sea.”

Yet, he continued, “When other people count sheep, or reach for the Halcion bottle, I make imaginary voyages — where the sea is always lightly brushed by a wind of no more than 15 knots, the visibility always good, and my boat never more than an hour from the nearest safe anchorage.”

Jonathan Raban was born on June 14, 1942, in Norfolk, England, to the Rev. Peter and Monica (Sandison) Raban and raised in vicarages. His father was an Anglican clergyman, and his mother wrote romantic short stories for women’s magazines before her marriage, enabling her to buy a black Austin 7 car with the money, Mr. Raban told Granta.

“Her letters to me at boarding school were writerly ones,” he said, “full of description and simile, so I guess something of that rubbed off on me.”

At the University of Hull, from which he graduated in the mid-1960s, Mr. Raban befriended the poet Philip Larkin, who was then the school’s head librarian. Another friend, the poet Robert Lowell, invited Mr. Raban to live at his house in London for a while in the 1970s.

Mr. Raban taught literature at Aberystwyth University in Wales and the University of East Anglia in England in the late 1960s and wrote fiction, radio plays for the BBC and criticism for London Magazine and The New York Review of Books.

He followed his first travel book, “Arabia Through the Looking Glass” (1979), with “Old Glory: A Voyage Down the Mississippi” (1981), which was inspired by his reading Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” as a boy. Instead of a raft, Mr. Raban traveled to cities and towns along the river in an aluminum boat with an outboard motor.

He wrote that the crudely drawn cover illustration of “Huckleberry Finn” that he had read at 7 years old “supplied me with the raw material for an exquisite and recurring daydream. It showed a boy alone, his face prematurely wizened with experience.”

“Cut loose from the world,” he added, “chewing on his corncob pipe, the boy was blissfully lost in this stillwater paradise.”

He is survived by his daughter, Julia Raban, from his marriage to Ms. Lenihan. His marriages to Bridget Johnson and Caroline Cuthbert also ended in divorce.

Since his stroke, which left him with the use of only one hand, Mr. Raban had worked on an autobiography, “Father and Son.” Instead of a computer, he used voice dictation software to write and edit the book, which he finally completed. It is to be published by Knopf in September, John Freeman, his editor, wrote in an email.

Mr. Freeman added, “It is one of the most miraculous feats of writing I’ve ever witnessed.”