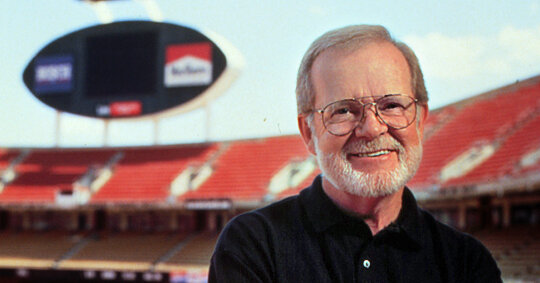

Ron Labinski, Who Designed a Cozier Future for Stadiums, Dies at 85

Ron Labinski, a visionary architect who a half-century ago foresaw a market for modern single-sport stadiums and then helped design them, replacing look-alike concrete bowls that had often inelegantly housed both baseball and football teams, died on Jan. 1 in Prairie Village, Kan. He was 85.

His wife, Lee (Beougher) Labinski, said the cause was frontotemporal dementia.

Mr. Labinski, who was believed to be the first architect in the United States to specialize in sports facilities, helped transform stadium design over 30 years, creating cozy, fan-friendly venues like Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore and Oracle Park in San Francisco.

At the same time, his designs brought a critical source of new revenue to team owners with club seats, built as exclusive sections with access to climate-controlled private lounges and restaurants.

“His forward thinking about how we watch games and how teams use their building, beyond what was happening on the field, was a real game-changer,” said Janet Marie Smith, who was a Baltimore Orioles executive when the team was planning Oriole Park, an urban ballpark with a retro brick exterior that was designed by HOK Sport, which Mr. Labinski helped found. Now 31 years old, Camden Yards is still considered one of the best early examples of the new wave of single-sport stadiums.

“He doesn’t get enough credit for putting the stake in the ground of the multipurpose stadium era,” Ms. Smith added.

Mr. Labinski helped usher in that era as the project architect of Arrowhead Stadium, which opened in 1972 as the home of the N.F.L.’s Kansas City Chiefs and the companion to Kauffman Stadium, the home of the baseball Royals. The facilities replaced a stadium that the Chiefs and Royals (and before them, the Athletics, before they moved to Oakland, Calif.) had shared.

While working on Arrowhead, Mr. Labinski starting looking at the national landscape of aging, multipurpose stadiums — whose round shapes precluded good sightlines for many baseball and football fans — and saw opportunity. He listed all the Major League Baseball and National Football League stadiums, the years they were built and when their leases expired, providing him with a guide to his future work.

“There was a huge bubble in the 1990s and a little past 2000, when all the lease agreements at these multipurpose stadiums were up,” Mr. Labinski told Sports Business Journal in 2010. “I recognized through all the conversations I was having with owners that the multipurpose stadiums were not the way they’d want to go in the future. They wanted out of those.”

His compendium became a to-do list for the next 30 years at architectural firms in Kansas City, most notably HOK Sport, a division of a St. Louis firm. (HOK Sport was renamed Populous in 2009 after a management buyout and Mr. Labinski’s retirement.)

He followed Arrowhead by designing Giants Stadium, which opened in the New Jersey Meadowlands in 1976 and became the home of the New York Giants and Jets until it was replaced by Met Life Stadium in 2010. He became friendly with Tim Mara, then the Giants’ co-owner, who introduced him to other N.F.L. owners. And by attending N.F.L. and M.L.B. meetings, Mr. Labinski learned what teams might want in stadiums in the future.

“I’d go with him to visit N.F.L. clubs,” Joe Spear, a longtime colleague, said in a phone interview. “And we were pitching renovations, like suites, which was his real entree into a lot of franchises.”

For his design of Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Fla., which opened in 1987 as the home of the Miami Dolphins, Mr. Labinski is credited with creating the category of club seats as a cheaper option for fans than expensive, enclosed luxury suites. Revenue from both the club seats and the suites helped Joe Robbie, then the Dolphins’ owner, finance the stadium’s construction. Club seats soon became essential parts of every stadium’s design.

Mr. Labinski played roles in the designs of other N.F.L. stadiums as well, including Bank of America Stadium in Charlotte, N.C., Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Fla., TIAA Bank Field in Jacksonville, Fla., and M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore.

“He greatly influenced the way N.F.L. stadiums appeared from the 1990s through the 2000s, especially with respect to their seating bowls,” Earl Santee, a longtime colleague of Mr. Labinski’s and a senior principal at Populous, wrote in an email, referring to the shape of the seating sections. “Lower seating bowls in N.F.L. stadiums were formerly contiguous, but Ron had the idea to create ‘neighborhoods’ of fans, providing different experiences in different areas.”

Ronald Joseph Labinski was born on Dec. 7, 1937, in Buffalo. His father, Raymond, was a wholesale food salesman; his mother, Bertha Labinski, was a homemaker. Ron was artistic from a young age, drawing houses, barns and windmills — and in one instance Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, showing a baseball leaving that beloved little bandbox.

“I guess you could say that was a sign,” he told The Kansas City Star in 2000.

After graduating from the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, with a bachelor’s degree in architecture, he spent six months in Europe studying architecture on a fellowship and two years in the Army at Fort Riley, Kan. He designed hospitals for a firm in Kansas City before being hired by Kivett & Myers, where he was assigned to the Arrowhead project.

After several years, he formed firm Devine, James, Labinski & Myers, which lost its bid to design the Hoosier Dome (where the Indianapolis Colts played until 2007) to a much larger rival, HNTB. But Mr. Labinski’s concepts for the stadium were impressive enough for HNTB to hire him, and he brought along several of his colleagues and set up a sports architecture practice within the firm.

He and other members of his group left HNTB after three years to join HOK, bringing about a dozen HNTB clients with them. HOK Sport became one of the foremost stadium and arena designers nationally and internationally.

The hallmarks of HOK’s designs include sightlines that provide the best possible views of games as well as vistas of what’s beyond a stadium — the skyline outside Oracle Park in San Francisco, for example, or the B&O Warehouse outside Camden Yards, or a panorama of downtown Denver and the Front Range mountains from rooftop cabanas at Coors Field. The designs are also distinguished by open concourses that let fans follow the action while buying food from a wide array of concession options.

In addition to his wife, Mr. Labinski is survived by his daughter, Michelle Embry; his son, Kent; two grandchildren, and his sisters, Barbara Maves and Marcia DePasse. He had been living in Fairway, Kan., outside Kansas City, before moving to a memory care facility in Prairie Village.

The prescience that Mr. Labinski showed in compiling his list of potential single-sport stadiums paid off in the 1990s when a tsunami of work came to HOK. He often traveled to find new business but continued to work on stadium and arena designs.

“His touch on the projects varied based on the project and client relationship,” Mr. Santee said in his email. “His mode of operation is consistent with how we operate today, where everyone in our leadership, since Ron started the practice, is working on projects.”

Mr. Labinski retired in 2000 and scaled back the scope of his architectural projects: He built a two-story addition to his house, a pagoda-like design studio for a neighbor, a playhouse for his granddaughter and a bed designed like a Ferrari for his grandson.